Abolition

Representations of Black Womanhood in the Anti-Slavery Movement

Black women held important roles in the abolition movement, or the movement to end slavery. However, they had limited control over their own representation. The imagery and objects used to promote abolition, often funded and designed by white activists, commonly reinforced a diminished view of Black women as “pitied” or in need of “saving.”

Please note that this exhibition contains content associated with difficult histories and historical trauma.

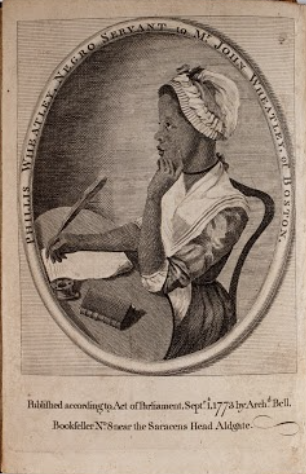

Poems on Various Subjects Religious and Moral

Phillis Wheatley, 1773

Poems was the first book of poetry published by an African American woman. Wheatley's sophisticated writing surpassed the expectations of her oppressors, including her enslaver, Boston Congregationalist John Wheatley. The engraved portrait of Wheatley in the frontispiece of the book, which depicts her like European authors of the time, emphasizes her genius, authenticity, and authorship.

"In every human Breast, God has implanted a Principle, which we call Love of Freedom; it is impatient of Oppression, and pants for Deliverance.

The pen and paper in the portrait of Phillis Wheatley shows her role as a writer. What would you choose to hold if someone painted your portrait?

Seal

Unknown maker, 1820-40

Reading “AM I NOT A WOMAN AND A SISTER” in reverse, this seal could be worn as a piece of jewelry or used to close a letter with wax. But who was this bauble for? Reflecting female abolitionists’ efforts for the cause, this is an image of a Black woman created by white activists primarily for white audiences. Despite its anti-slavery message, situating the enslaved Black woman in a kneeling position signifies submission instead of resistance in relation to the assumed white wearer.

Compare the image of Phillis Wheatley to that of the woman on the seal. How did these artists communicate a message with these images?

Liberty Displaying the Arts and Sciences

Samuel Jennings, 1792

Jennings’s allegorical painting is an early artwork promoting the abolition of American slavery. The woman on the right stares slightly upwards with hard-set eyes. She is a mother—her right arm wraps around the young child in front of her, who reaches out a pair of shackled wrists. Within this scene lies the paradox of early abolitionist movements: How could freedom be “given” back by the same people who took it away?

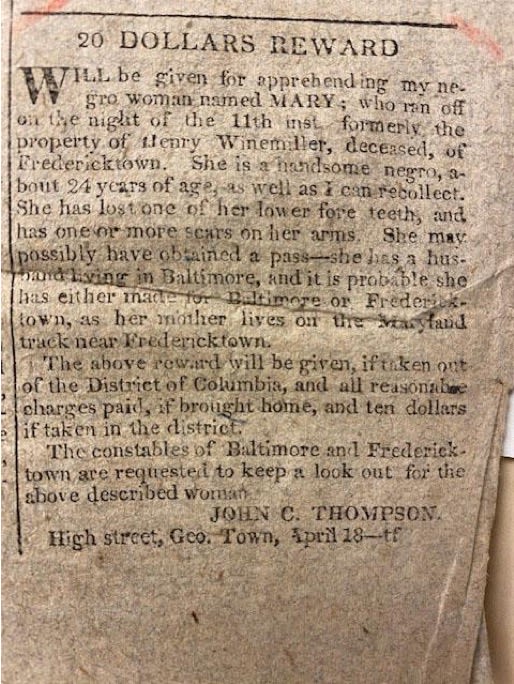

Advertisement

National Intelligencer, Washington D.C., April 25, 1815

Mary, an enslaved woman seeking freedom, appeared among tavern and estate advertisements when John C. Thompson listed a description of her body as a “handsome negro, about 24 years of age.” Mary’s labor scars and malnutrition are the only ways her enslaver chose to represent her, besides calling her “former property.” How would Mary describe herself? Did Mary finally find freedom with her husband in Baltimore or with her mother some 50 miles away in Frederick, Maryland?

This exhibition is presented by Winterthur Museum, Garden & Library. To learn more, visit www.winterthur.org.